Does studying magic make one a better or more creative scientist, technologist, researcher, or teacher? Best-selling creativity author and Wharton professor Adam Grant has an answer, and it’sa resounding yes! As covered in Forbes, Grant says that artistic hobbies train us to think creatively and give us access to new ways of solving problems. For example, Einstein described his theory of relativity as a musical thought, and Galileo recognized the moon’s mountains through a telescope because of drawing instruction that made him mindful of shading.

At the top of Grant’s list of creativity-enhancing hobbies is practicing magic. Getting good at the element of surprise, “helps with making new scientific discoveries. It also reinforces curiosity, focused attention, and the desire to have an impact on an audience.”

Magic at Stanford

I’ve found several stellar examples of accomplished scientists at my Alma Mater Stanford (MBA ’91) who demonstrate how studying performance magic has been a critical training ground or source of inspiration for their success in scientific research, inquiry – and their careers.

A cancer researcher sharing how magic can make science better

Parag Mallick, PhD, currently an Associate Professor at Stanford’s School of Medicine, is also a professional magician, as well as Founder & Chief Scientist at Nautilus Biotechnology, a company pioneering a single-molecule protein analysis platform for quantifying the human proteome. A long-time member and performer at The Academy of Magical Arts, aka The Magic Castle in Hollywood, Mallick also once shared the concern that Persi Diaconis had early in his career – that being open about one’s interest in magic with academic colleagues might best be avoided due to how it might be perceived.

For years, Mallick kept his two worlds of science and magic separate. He was concerned that scientists wouldn’t take him or his research seriously, and that magicians and other performers he worked with would question his dedication to his craft. A few years ago, he reconciled this and unified his dual life, and the change has been overwhelmingly positive.

“Being able to talk about magic openly and discuss concepts from magic in science – like the fundamentals of perception and misperception and how that might influence scientists’ ability to interpret data – it’s really made me both a better scientist and a better magician.” – Parag Mallick, Associate Professor at Stanford School of Medicine

Mallick now embraces sharing with academic colleagues that he is a magician – and that he believes the study of magic can improve and inform scientists’ work. Mallick developed an academic presentation entitled “Your Brain Is Deceiving You: A Magician-Scientist’s Perspective on How to Do Better Science” that he’s delivered at MIT, ASU, and Cambridge to enthusiastic audiences. When Parag gave his talk at MIT, it was the first time he received a standing ovation for an academic lecture. Mallick has found that sharing his interest in magic with academic colleagues has helped his science and was liberating.

The best scientists and magicians share a healthy disregard for the impossible

Mallick, who arrived at Stanford a decade ago, shared some insights on how magicians and scientists look at the world in a similar way. “As a scientist, you are constantly looking at and dealing with the impossible – and then making it possible. For example, 25 years ago sequencing the genome was impossible, yet today it’s commonplace.”

Mallick says that this process is quite like what magicians deal with when they make “impossible” things appear possible. “The very best scientists and magicians share a healthy disregard for the impossible and a near-obsessive attention to detail,” says Mallick. In addition, to achieve the highest levels of success, both scientists and magicians must become comfortable with a process that repeatedly involves being wrong and failing along the way.

Magic and science have a long-intertwined history

A few hundred years ago, magicians were the popularizers of science, blurring the line between performing magic as entertainment and demonstrating new “scientific curiosities.” There are splendid examples of prominent magician-scientists who became influential advisors to European monarchs during the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries. For example, John Dee, one of the most learned men of his day (1527 – 1608), straddled the worlds of magic and science. He was known as an astronomer, mathematician, navigator, alchemist, spy and “celestial necromancer” when he became the Scientific and Medical Advisor to Queen Elizabeth I. As Arthur C. Clarke pointed out sometime later, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”

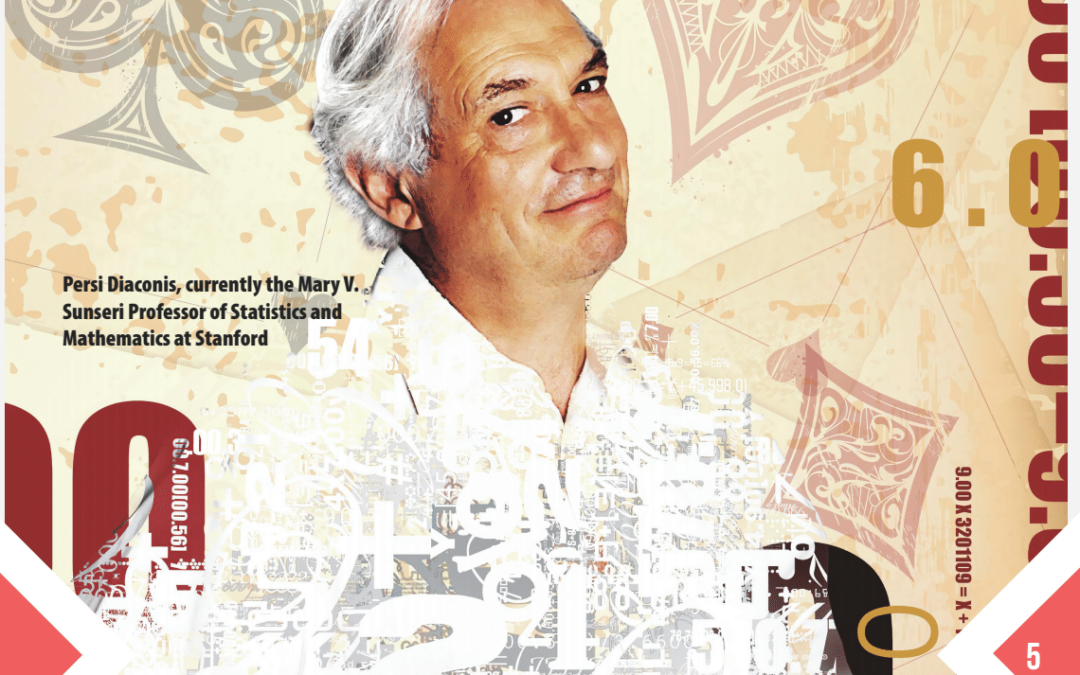

Mathematical achievement inspired by card magic

When Persi Diaconis, currently the Mary V. Sunseri Professor of Statistics and Mathematics at Stanford, was a teenager, he ran away to study and perform magic with legendary magician Dai Vernon. Diaconis’ study of a deck of cards and magic led to a fascination with numbers and math. He was a professional magician for many years, then went on to study mathematics at Harvard, came to Stanford in the mid-1970s, and won a MacArthur Fellows “genius” grant back in 1982.

A search for the hidden workings of magic led Diaconis to math

Diaconis has attributed his interest and achievements in mathematics to his study of magic and the mathematics of a deck of cards. According to a profile in the Chronicle of Higher Education, when Diaconis first came to Stanford he planned to keep his magic background a secret from academic colleagues. His concern was that they wouldn’t take seriously a man of hocus-pocus who did research on card shuffling.

Then he stumbled upon a book in the Stanford library that changed his mind. It described an experiment by one of his intellectual heroes, French mathematician Paul Lévy, analyzing the phenomenon known as perfect shuffling – in which a standard deck of cards is carefully shuffled eight times and ends up returning precisely to its starting arrangement. “I let out a whoop,” Diaconis said. “I thought, if Paul Lévy can study perfect shuffling, I can say I study perfect shuffling. I wrote up my work on perfect shuffling, and it got on the front page of The New York Times.” Since then, Diaconis has continued to leverage what he knows from the magic world to inform both his research and teaching.

Over the years, Diaconis has taught numerous classes at Stanford on the mathematics of magic tricks – including freshman seminars, graduate classes, and as part of multi-disciplinary programs – with magic woven in to bring the mathematics to life. Persi enjoys performing magic tricks for students when it helps demonstrate and teach the principles under study, and these classes have been, not surprisingly, very popular with students.

A graduate course on the mathematics of card shuffling

Over a Peking Duck lunch in a quiet neighborhood near the Stanford campus, I asked Persi how magic is informing and inspiring his work today. “More than usual,” Persi replies. “I’m currently focused on finishing my next book, a graduate course textbook on The Mathematics of Shuffling Cards.” Several of the book’s chapters are based on magic-related principles, and Persi enthusiastically talked about his research into obscure magic journals of nearly a century ago that is informing his work today.

Persi has long stayed abreast of developments in the magic community by, as they say, reading the literature, as well as by maintaining close relationships with many of the world’s top magical thinkers. Following a long-held magicians’ tradition, Persi is an avid collector and has one of the largest libraries of magic books and periodicals on the West Coast with more than 15,000 items in his library.

How relevant is magic to questions that science is examining today? The study of magic tricks based on complex mathematical principles, according to Diaconis, “can be applied to make and break codes for spies and for analyzing DNA strings. The magic angle suggests wild new variations. Some lead to math problems that will be challenges for the rest of the century.”

“…the mathematics behind this card trick underlies a promising technique for reading DNA.” – Persi Diaconis, Prof. of Math, Stanford University

A leading magician helping professors teach more effectively

A different way magicians and scientists collaborate is exemplified by magician Vito Lupo. Lupo was the first American to win the prestigious international Grand Prix of Magic competition and later spent a decade as a consultant to Disney, designing illusions to make some of their highest profile events more magical.

Lupo, who currently resides in Venice Italy, was recently invited to participate in Padua University’s Teaching 4 Learning project, which promotes innovative methods to improve and modernize teaching. Lupo’s talk, “Magic and Teaching…Magic Transformations,” gave a magician’s perspective on how to engage students and teachers. The lecture was well received by Padua’s faculty, and Lupo was energized by experiencing how the magician’s perspective can catalyze more effective education and communication.

A neuroscientist-surgeon who learned skills and confidence from practicing magic

Prominent Stanford neuroscientist, James Doty, MD, Clinical Professor of Neurosurgery at Stanford School of Medicine, is the author of the best-selling book Into the Magic Shop: A Neurosurgeon’s Quest to Discover the Mysteries of the Brain and the Secrets of the Heart. Doty has also declared his appreciation of studying magic on his path to becoming an accomplished neurosurgeon. In his book, Doty partly attributes his skill as a surgeon to the confidence and dexterity he learned when diligently practicing difficult sleight-of-hand magic in his youth.

The influence of magic on neuroscience

Over the past decade, significant research in neuroscience has been driven by scientists inspired by magic and doing research in collaboration with magicians. A major turning point came in 2008 with the publication of “Attention and awareness in stage magic: turning tricks into research” in the journal Nature Reviews Neuroscience, written by neuroscientists Stephen L. Macknik and Susana Martinez, along with a cadre of professional magicians including Teller and Apollo Robbins. Macknik and Martinez are Laboratory Directors at the Barrow Neurological Institute in Phoenix, Arizona, and are also members of the Academy of Magical Arts. The authors state:

“By studying magicians and their techniques, neuroscientists can learn powerful methods to manipulate attention and awareness in the laboratory. Such methods could be exploited to directly study the behavioral and neural basis of consciousness itself, for instance through the use of brain imaging and other neural recording techniques.”

This work led to the publication in 2010 of Sleights of Mind: What the Neuroscience of Magic Reveals about Our Everyday Deceptions, which helped popularize the legitimacy of scientific researchers studying magicians – and their semi-guarded body of knowledge on the theory of perception, deception and illusion – to help advance scientific research in this era. Teller, the quiet member of the dynamic Penn & Teller magic duo, explains it this way: “At the core of every magic trick is a cold, cognitive experiment in perception.”

Can studying magic increase the odds of a scientist winning a Nobel prize?

What makes one an Olympic medalist, or a Nobel prize-winning scientist? While part of it is winning the genetic lottery, are there unexpected, non-traditional activities or skillsets that up the odds for exceptional achievement? For example, according to University of Michigan research, scientists who are musicians are twice as likely to win a Nobel prize. The hotly debated and oft-reputed research finds that scientists who are amateur magicians are 22 times more likely to win a Nobel prize. Even if this research is highly skewed, it suggests that scientists with creative, performance-oriented pursuits (music, magic) outperform scientists who don’t.

Even as we live in an era where new “technological marvels” that would have been seen as utterly “magical” just a few years ago become more and more commonplace, the influence of the conjuring arts on science and technology is on an upswing. When magicians share their knowledge with scientists, technologists and researchers, new possibilities are revealed.

We believe the time is ripe for a symposium where the top minds in the magic world collaborate with researchers, technologists, and academics to progress this unique confluence. In fact, we’ve got one in the works – if you’re interested in supporting such a symposium, contact info@themagicsymposium.com.

About the Author

Adam Fleischer earned his B.A. in Ancient Studies, focusing on a cross-disciplinary examination of the philosophy of Socrates, from Columbia University in New York City in 1987. At the same time, he was a magic impresario producing The New York Magic Symposium, an international magic convention, and publishing magic’s first full-color glossy magazine, The Magic Manuscript. He also produced off-Broadway theatricals in New York City and prime-time TV specials, all before attending Stanford’s Graduate School of Business and earning his MBA in 1991. He then founded and was CEO of E.ON Interactive Design, one of Silicon Valley’s earliest boutique creative interactive marketing agencies. Today, Adam serves as a technology marketing consultant with clients including Microsoft, IBM, Panasonic, SAP, Analog Devices, Arrow Electronics, Coupa, MuleSoft and other technology leaders.

Recent Comments