The magician introduces three cups and some little balls. She waves her magic wand and commands the balls to ma- terialise from her hands and rematerialise under the cups. The props seem possessed by supernatural powers as they appear, disappear and penetrate solid matter at the mere whima of the magician. This unearth- ly choreography ends with pieces of fruit appearing under the cups where the balls once were. The spectators applaud after wit- nessing this ancient miracle. Yet, although they are both fooled and entertained, a nagging thought lingers in their minds: How did she do it?

questions beyond how she performed the trick. The psychologist wonders how the per- former so easily deceived his mind. How can our minds see something that contradicts our common-sense view of the world? The profes- sor in humanities also enjoyed the show. She ponders the cultural significance of magic and why it has remained popular for millen- nia across different cultures. Her husband is an occupational therapist at the local hospital and an amateur magician. He admires the complex hand-eye coordination needed to perform this trick and contemplates how magic tricks can help his patients.

This anecdote illustrates how magic per-formances can have different meanings, depending on the viewer’s perspective. These paragraphs also show that the question of how magicians accomplish a magic trick is only one of the wide variety of possible questions. This article explores some of these questions and looks at the complex rela- tionship between magic and science.

How Magic Informs Science

Performing magic is essentially an anti-scientific endeavour. A magician is a performer who creates illusions that break the known laws of nature. Even though the central premise of magic as a performance is to flaunt with our scientific understanding of the world, magicians nevertheless use the principles of science to create the illusion of magic. The magician in the introduction is fully aware of the psychological aspects of her performance by managing the audience’s attention. Other magicians extensively use mathematics, engineering, information technology, linguistics, sociology or performance studies to present a world where the impossible becomes seemingly possible. The relationship between science and magic is thus bi-directional. Magicians use science to create the illusion of supernatural magic, while scientists study magicians and their craft to learn more about the world around us.

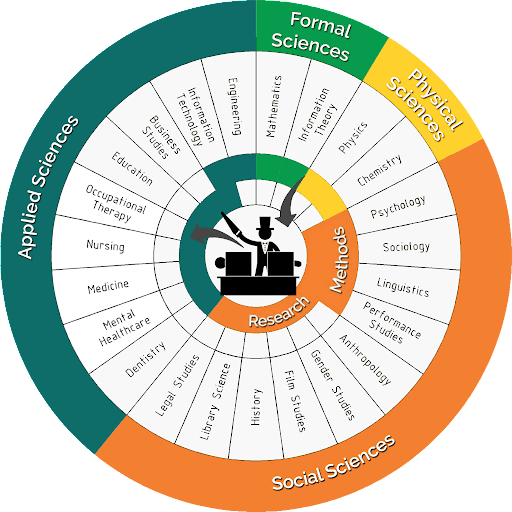

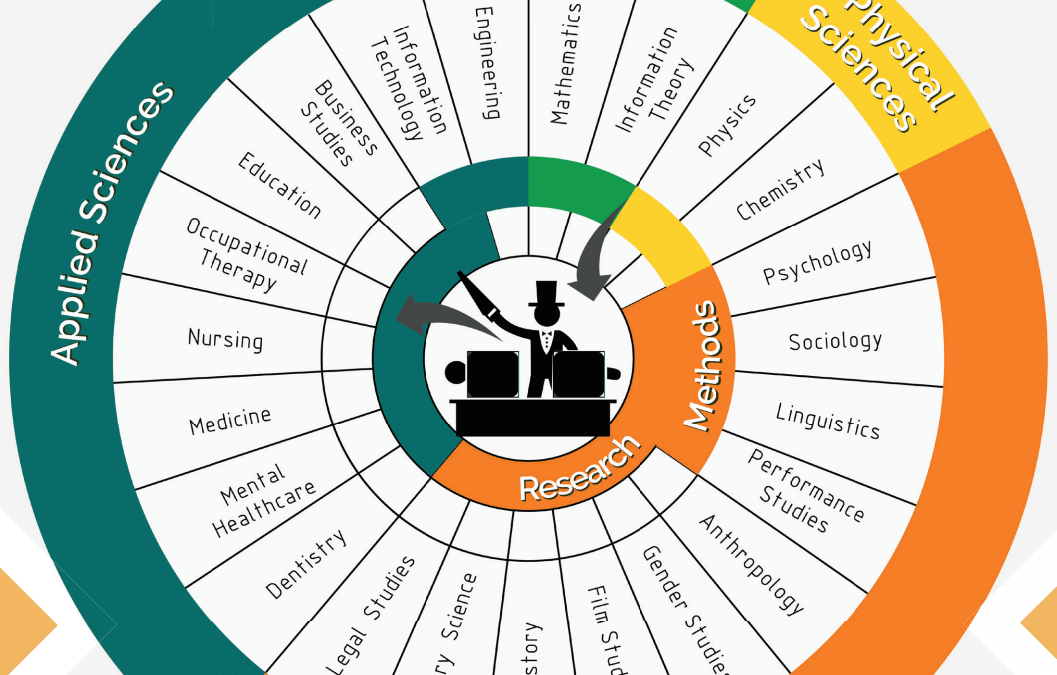

The diagram above visualises this bidirectional relationship. The outer circle shows the types of sciences involved with magic: formal, physical, social, and applied sciences. The formal sciences, such as mathematics, form the foundations of science. The physical sciences, such as physics and chemistry, describe the material world. The social sciences study the behaviour of human beings, either as individuals or in groups. The social sciences also study the artefacts of human cultures, one of which is theatrical magic. The second ring lists the individual sciences where scholars and professionals have published about theatrical magic. Each of these sciences has a different relationship with theatrical magic. Magicians use science as layers of deception (the methods ring), while scholars develop scientific perspectives of magic (the research ring). Some sciences, such as psychology and performance studies, are both a method of magic and a field of study.

An Academic Bibliography of Magic and Science

The circle diagram provides a taxonomy of the magic of science and the science of magic that emerged from extensive bibliographical research into magic. I discovered the first scientific paper on magic when writing my dissertation about business studies. This paper showed how magic tricks can help to explain abstract concepts of management. Finding this paper was a welcome distraction from my primary research. I subsequently started a fascinating exploration into the world of science and magic by developing a bibliography.

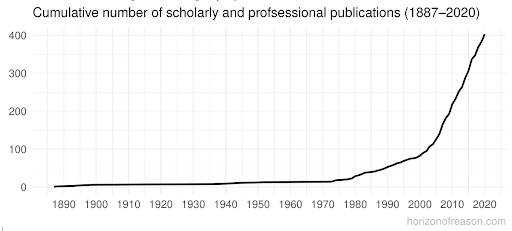

The bibliography of the science of magic currently includes more than four hundred entries. The scientific research into magic is often undertaken out of an interest in magic itself, but also uses magic performances as a research method to learn about the world in general. For magicians, this research is valuable and exciting. These scientific findings enriches their art and perhaps helps them fine-tune their techniques to improve the deceptiveness and entertainment value of their tricks. For scientists, magic is an exciting field of study and experimental modality that helps us to understand the world.

For the full academic magic bibliography,

see: https://horizonofreason.com/magic/magic-bibliography/.

Formal Sciences

The formal sciences form the foundations of all the other sciences. Subjects such as logic and mathematics provide the building blocks of science. Magicians often rely on mathema- tics as a method to entertain their audiences. Even the greats of magic, such as David Cop- perfield, use self-working mathematical tricks.

Mathematical magic tricks broadly fall into three categories. Most such magic entails self-working routines that use number theory. sociology or performance studies to present a world where the impossible becomes seemingly possible. The relationship between science and magic is thus bi-directional. Magicians use science to create the illusion of supernatural magic, while scientists study magicians and their craft to learn more about the world around us.

The diagram above visualises this bidirec- tional relationship. The outer circle shows the types of sciences involved with magic: formal, physical, social, and applied sciences. The formal sciences, such as mathematics, form the foundations of science. The physical sciences, such as physics and chemistry, des- cribe the material world. The social sciences study the behaviour of human beings, either as individuals or in groups. The social sciences also study the artefacts of human cultures, one of which is theatrical magic. The second ring lists the individual sciences where scho- lars and professionals have published about theatrical magic. Each of these sciences has a different relationship with theatrical magic. Magicians use science as layers of deception (the methods ring), while scholars develop scientific perspectives of magic (the research ring). Some sciences, such as psychology and performance studies, are both a method of magic and a field of study.

The Bibliography of Magic and Science

The circle diagram provides a taxonomy of the magic of science and the science of magic that emerged from extensive bibliographical research into magic. I discovered the first scientific paper on magic when writing my dissertation about business studies. This paper showed how magic tricks can help to These are the well-known tricks that use patterns and properties of numbers to create seemingly impossible outcomes. Less common are magic tricks that use geometry, with the missing square puzzle as the most popular implementation. The third category of mathematical magic tricks uses topology. Classics, such as the linking rings, have a topolo- gical theme. Linking two rings without cutting them is only possible in a world with more than three spatial dimensions. Some magic tricks, such as the legendary Afghan Bands or rubber band magic, use topology as a method.

Natural Sciences

The science of nature seeks to develop models to explain and predict the physical and biological world. Magicians liberally use the principles of physics and chemistry to create their illusions. Magical engineering uses optics, hydraulics and electronics and anything else that can help create a magical effect. The scientific literature in this genre does not research magic itself but mainly describes how teachers can use magic tricks to help students understand the principles of nature.

Social Sciences

The social sciences are a broad group of scientific interests that study all aspects of human individuals and collectives. This area of research is so wide that the space available in this article can barely skim the surface. Psychology is the mother of all sciences of magic. The scientific study of magic is almost as old as psychology, with the first papers published in the 19th century. More recently, the number of articles on this topic has seen exponential growth. Gustav Kuhn is one of the drivers of this research through the Magic Lab at Goldsmiths University. The broad question of interest in most of these studies is how magicians deceive people. This research is interesting for magicians who like to per- fect their techniques. More importantly, this research also generalises broader questions about how humans perceive the world.

Sociology and anthropology have a long-standing interest in magic. Initially, anthropologists directed their attention toward magicians and shamans in traditional societies, some of which use sleight-of-hand as part of their rituals. Since decolonisation, anthropologists have focused more on wes- tern societies, including theatrical magicians. The main question of interest for sociolo- gists and anthropologists is how magicians organise themselves, transmit their secret knowledge, and the meaning of magic within contemporary society.

The field of performance studies is a signifi- cant aspect of the social sciences researching magic. The underlying question in this field of study is the place of magic within the per- formance arts. Traditionally, literature The Huddersfield University publi- shes the Journal of Performance Magic, dedicated to publishing articles on theatrical magic that provide a wide perspective of the art of magic.

Also linguists have directed their attention to magic by looking at how the words used in performances enhance the deceptive quality of a magic trick. Linguistic interest in magic is not only theoretical. Magicians have enhanced the English dictionary with words and phrases such as “gimmick” and “smoke and mirrors”.

Performing magic seems to be a male-do- minated activity, with only a fraction of magicians being female performers. Several scholars in gender studies have tried to find an answer to this imbalance. Fortunately, the number of female magicians is gradually increasing, enhancing our craft’s diversity.

Film studies analyses cinema from the past and present and is as such an offshoot of per- formance studies. French magician Georges Méliès is the father of all special effects. He invented a lot of new techniques in the early days of cinema. Cinema and magic still have a lot in common in the 21st century. They both present the viewer with a world where the seemingly impossible becomes possible.

The historiography of magic (the science of writing the history of magic) has evolved much in the past decades. Early magic history books focus on the magician as the story’s hero. Contemporary history books focus less on individuals and place magicians and their art within the context of the society in which they live.

Lastly, scholars in legal studies have inves- tigated issues with intellectual property in magic. The magical literature is littered with disputes about originality and claims of plagiarism, which makes it a fertile field for experts in this area.

Applied Sciences

The applied sciences, such as teaching, engineering and health care, use the formal, natural and social sciences as mechanisms to improve reality. For example, teachers trans- mit knowledge, engineers create the physical world we live in, and medical professionals help us live long healthy lives. The magic lite- rature in the applied sciences describes how magic tricks and the methods of magicians can help these professionals quest to improve the world.

The most common applications of magic are in education and health care. For example, mathematics and science teachers use magic tricks to explain otherwise abstract concepts and enhance the learning experience. Many magic tricks that use physics, chemistry or mathematics are ideal vehicles to engage students in the subject. Nurses, dentists and doctors use magic tricks to reduce anxiety in children before treatment. Magic in health care is not only a passive form of entertainment to engender positive emotions in patients. Performing magic tricks by the patients themselves can increase their self-esteem. Patients of occu- pational therapists can use magic to improve their manual dexterity. Programs, such as Kevin Spencer’s Healing of Magic, trains thera- pists to use magic in their practice.

Also computer scientists have started expe- rimenting with magic tricks. Both magicians and software designers create virtual realities. The computer screen is the theatre of the software developer, and deception is also an integral part of Artificial Intelligence and robotics. For example, you might think that you are chatting to a person while in actual fact, you are responding to a string of words generated by an algorithm. The computer has no idea what these words mean, and we are deceived into believing we converse with a person. Software developers don’t neces- sarily use the same techniques as magicians, but perhaps they should embrace them to improve the deceptiveness of their software.

New Avenues of Inspiration

This article barely touches the surface of the amount of available literature about science and magic. We can conclude from this safari into the bibliography of the magical sciences that there is no such thing as the science of magic. Eugene Burger used to say that the house of magic has many rooms. This analogy does not only apply to magicians but can ea- sily be extended to the sciences. Likewise, the house of science also has many rooms and thus provides multiple perspectives on magic. Reading scientific literature about magic is not only beneficial for experts in their respective fields. Magicians can learn from the science of magic as it can enhance their methods, provide inspiration for their scripts, and generally increase appreciation of the art. For scientists and professionals, studying ma- gic is a rewarding activity that can inspire and revitalise the mind and open new avenues of inspiration.

Recent Comments