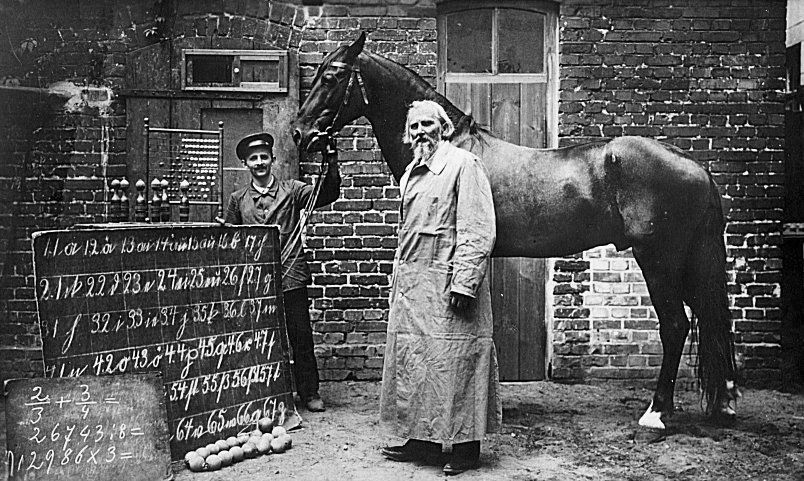

Wilhelm von Osten was a mathematician and schoolteacher living in Germany in the early 1900’s. He was also an amateur horse trainer. At that time, people were becoming interested in how intelligent animals were. Von Osten experimented to see if he could teach his horse math. To his amazement and excitement, he was able to teach his horse how to do calculations, read and spell, and even understand German.

He would ask his horse a question such as “What is two plus two?”, and the horse would tap its foot four times. Von Osten named his horse “Clever Hans” and traveled around Germany presenting Hans to the public. This caught the attention of skeptical scientists, and in 1907 a formal investigation was organized and led by psychologist Oskar Pfungst.

Clever Hans almost always gave the right answer when he could see Von Osten, but also gave the right answer if someone else asked a question, which proved Von Osten was not intentionally secretly signaling Clever Hans or trying to trick his audience. Von Osten genuinely believed Clever Hans’ abilities. Investigator Pfungst was truly baffled by the demonstrations, and even more so when the first few controlled experiments failed to stump Clever Hans.

Neither Von Osten nor Pfungst were magicians, but had they been they might have discovered Hans’s secret much faster – Clever Hans was responding to very subtle non-verbal cues which the questioners were unknowingly signaling Hans. Eventually Pfungst figured out how to signal the horse. By slightly raising his eyebrows, he could get Hans to give any response he wanted.

There are so many subtle ways humans interact and communicate with the world around us that the study of magic makes us aware of. Magicians learn to intentionally and gently guide their spectators to select a card or object without their spectator’s knowledge that they are being influenced. On the other hand, there are unintentional signals magicians sometimes telegraph to their audience. A magician’s technique of secretly palming a card can be perfect and even invisible to a camera. But should the magician feel even a little doubt or guilt and think the spectator saw what they did, the spectator can sense something happened and the magic will be diminished.

Studying and performing magic is one of the best ways to understand these human influences and subtle interactions and can benefit scientists. Are you effectively communicating your thoughts and ideas? Are you listening to others and picking up on their reactions? Are you deceiving yourself?

Who is easier to fool: a ten-year old or a scientist?

Here is a fun question to ask a kid. If you write down all the numbers from 1 to 100, how many times does the number 9 appear? For example, 9, 19, 29, etc. This is an easy question to answer, and you can easily use your fingers to count, so quickly do this now and come to a total before you read on.

Every magician knows that it is much harder to fool a ten-year old kid than an adult. In fact, the “smarter” or more “knowledgeable” a person is, the easier it is to fool them. But why? Magic is based on hidden assumptions and conclusions that our minds automatically make. These assumptions are based on knowledge and experiences. For example, sitting down at a dinner table you automatically and without thinking assume the white dish is the same white color on the underside, that it is not attached to the table, that it is ceramic and not painted lead, etc.

Magicians take advantage of these assumptions and strive to make things appear “ordinary” when in fact they are gimmicked. The older and “smarter” a person becomes, the more knowledge and life experiences they have and the quicker their minds automatically make assumptions. It is very difficult for anybody, including magicians, to look past these automatic assumptions as we are all human and assumptions are programmed into our brains, probably for survival or other reasons. The question is how to bypass this mechanism and train yourself to look at everything and see things in a different way.

When you ask the question, how many times the number 9 appears from 1 to 100, most people will answer 11, which is the wrong answer. The correct answer is 20. Most people quickly get 9, 19, 29, 39, 49, 59, 69, 79, 89, and 99, but for some reason miss 91, 92, 93, etc. Can you learn to not miss something so seemingly obvious and invisible, these “blind spots”? The more you know and think about magic, the more you become trained to be more watchful and cautious in your observations and answers.

Magic teaches us that things are not always what they appear to be, and by performing magic it allows us to watch first-hand how people’s minds work and the assumptions they make when they are fooled. Because the magician knows exactly how the tricks they perform work, it is often amazing for them to hear the spectators’ explanations or theories of how they were done. Each trick performed is a kind of controlled experiment by the magician of a spectator’s thinking process. Also, after performing a trick, magicians usually analyze their performance based on their audience’s reactions to see what worked and what didn’t, and then they try to tweak the performance of the trick to make it stronger.

All magicians are sometimes fooled by a trick or performance by a fellow magician. This allows the magician to analyze their own mind and thinking process. They will walk away completely fooled and will think to themselves, what fooled me and where were my blind spots? Often magicians are fooled by tricks or methods they know and have even used themselves, but because something was slightly changed, they didn’t see it.

One can be fooled by physical gimmicks such as a trick cards or a hidden thread, or you can be fooled by subtle interactions such as misdirection or being psychologically manipulated, or a combination of both. Magic is one of the best ways to exercise our brains and expand our creativity because we see and learn so many tricks and principles.

“Thinking Outside of the Box”

Creativity is about looking at the world in a different way; and studying and performing magic makes one more creative. Magicians don’t want their spectators to figure out their tricks, so they are constantly trying to intentionally create “blind spots” for their spectators. These mental blocks are like writer’s block or creative blocks.

An exercise sometimes practiced when creativity is attempted to be taught is to write down as many things you can do with a paper clip except clip papers. The average person will come to only a few answers, whereas the more “creative” person will think of many more ideas.

A question that is often asked is, can creativity be taught, or can any person learn to “Think Outside the Box”? One of the things I have done to try and teach myself to be more creative is to collect novelty pens. Not just ordinary pens, but ones that are novel, such as the way they fold, an innovative mechanism, an unusual theme or styling. To me, it’s not a collection of pens, but it is a collection of ideas. How do you take a simple object such as a pen and make it interesting, inventive, and/or unusual? Different solutions to the same problem – design of a pen.

There are two kinds of ideas, or solutions, to problems. The first are ideas that you could have thought of had you been given the problem, for example, design a pen. The second are ideas you never would have thought of. Even if you had worked on the problem of designing a pen and thought about it for many years, some ideas would have never come to you. These are the “AHA” ideas, breakthroughs that require “thinking outside of the box.” They are the most valuable because they open new doors in your mind and get stored in your subconscious for later use. I believe the more ideas and “outside the box” solutions to problems you are exposed to, the more creative you will become.

Magic is full of “AHA” ideas and principles. Studying magic supplies your subconscious with much food for thought and later use, and performing magic allows you to put these “AHA” ideas to use.

“Blind Spots”

This true story has a big blind spot like the question previously asked about how many 9’s appear in the numbers from 1 to 100. During World War II, the Statistical Research Group at Columbia University was the most extraordinary group of mathematicians and statisticians ever organized at that time. They worked closely with the military to solve problems. For example, the loading order of ammunition on planes was worked out by the group. Because many planes were being shot down, the military wanted to find a way to reinforce the planes. When bombers returned from missions, many would be covered with bullet holes. The bullet holes were not evenly distributed around the plane, but were concentrated on the fuselage and wings, almost twice as much as places like the engines.

The group came to the obvious conclusion that they needed to reinforce the fuselage and wings with armor because these areas were taking the most fire. Exactly how much more armor should be added to those parts of the plane? You need to be precise as to not add too much additional weight that might affect the balance of the flight or other factors that need to be considered.

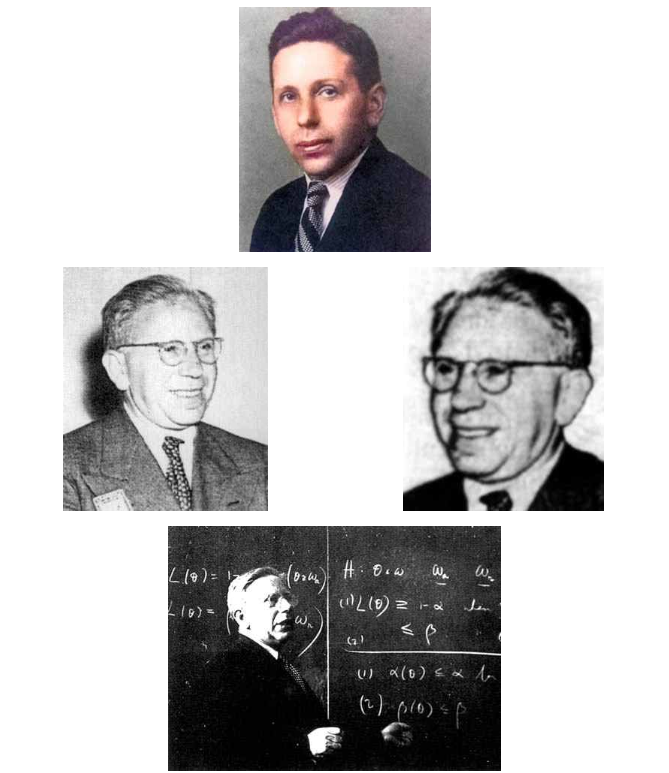

Hungarian born Abraham Wald worked with the group and was asked to figure out the calculations. Wald told the group they were completely wrong in their observations about the bullet holes being mainly on the fuselage and wings, and that the bullet holes were in fact evenly distributed all over the planes, including the engines, fuselages, wings, and the entire aircraft. How could Wald defy the obvious evidence that all these smart mathematicians observed? What blind spot did he see that the other geniuses missed?

Although Wald was not a magician, he was thinking like a one. Wald was looking at the invisible. The armor, said Wald, doesn’t go where the bullet holes are. It goes where the bullet holes are not – which is on the engines. But why?

Bullets holes were not found on areas like the engines because those planes were shot down and did not return home! The planes that had many bullet holes on the fuselage and wings proved that these were not the weak areas because they made it home without being shot down.

Wow! This is a real “AHA” idea! Imagine how useful it is to have hundreds of these “outside the box” ideas stored in your subconscious. Whether you are a scientist, magician, or just an ordinary person, it will make you more creative. I know it has for me.

——————

Mark Setteducat is a magician and inventor of magic, games, and puzzles. He has been issued 19 US Patents and over 50 of his creations have been marketed by companies worldwide. He is the author of “The Magic Show,” an interactive book that performs magic. In 2014, the Academy of Magical Arts awarded him a Creative Fellowship and lifetime membership to the Magic Castle, Hollywood, California.

Images

From Mark Setaducati-

I think most of these are public domain or are OK to use

Clever hans:

Abraham Wald

Recent Comments